The Importance of Reading: A Reading Love Letter

Laura Benson

Director of Curriculum and Professional Development

Books made me a TCK (third-culture kid) before I became one in real life. The first book I remember most in becoming a person of another culture was Fairy Tales from the Arabian Nights. Lifting myself out of southern California through the words of the authors of these Middle Eastern tales, I was awed by Sinbad the Sailor, Ali Baba, and the Forty Thieves and, of course, Aladdin and the Magic Lamp. I loved walking in the souls of others facing their challenges and, over time, came to understand our connections. As a girl, I never imagined I would live my own Arabian nights, first through my father’s job first and then my own.

Even before I knew her as an author, books helped me live Katherine Paterson’s advice: “If you don’t read, you’ll only be as big as your own life and your experiences. Books give us other centuries, other cultures, all kinds of people that you wouldn’t otherwise know.” Reading has constantly expanded my world. Reading has been and continues to be my comfort, compass, and conscious. In times of loss and grieving, in periods of discernment, and to close each day, I turn to reading. I am always happiest when right in the middle of a big fat book.

Books and reading teach us that we are not alone. We go into ourselves when reading. But there we find another self – our reader self. The internal dialogues we have with the words of the author and ourselves are part awakening and part fellowship. It’s hard to feel entirely alone as a reader.

Lately, I have learned about some additional gifts of reading. New studies have identified very good news for readers, especially life-long readers. Individuals with high lifetime levels of cognitive activity show slower decline, despite the presence of underlying pathology (Jacobs, 2017). “Habitual participation in cognitively stimulating pursuits over a lifetime might substantially increase the efficiency of some cognitive systems,” writes a research team led by neuropsychologist Robert Wilson of Chicago’s Rush University Medical Center. This efficiency apparently counteracts the often-devastating effects of nervous system diseases. “Asking ourselves, can we do anything to slow down late-life cognitive decline, the results suggest yes—read more books, write more, and do activities that keep your brain busy, irrespective of your age.”

Knowing the essential vitality and utility of reading in our lives, here are a few of the essential experiences children need to flourish as readers and from the importance of reading and from their earliest years until they leave your home to head out on their own:

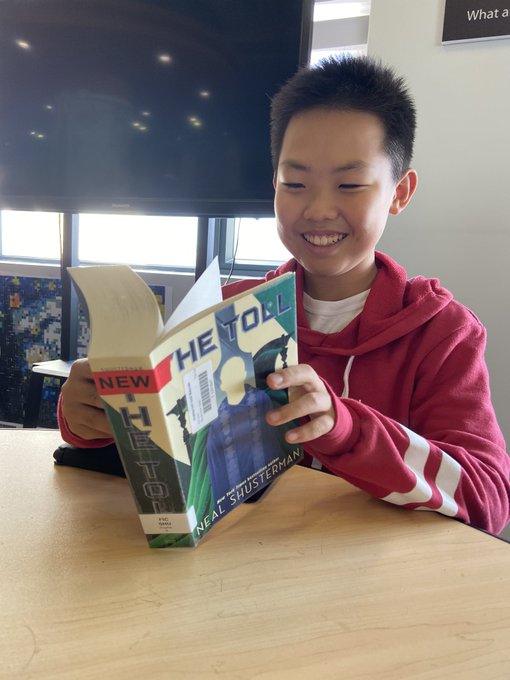

Let children read.

Engage the children you shepherd, whether teacher, administrator, or parent, in daily doses of reading with you and by reading on their own. This helps reading be something they own and look forward to each day. It becomes part of them and helps to shape their identities by fueling their passions and soothing the rough parts of life, too.

Books in hands. This is where it all begins. This is where it grows over time. From my forty years as an educator, especially as a literacy specialist, I have witnessed many reading wars and engaged in numerous passion fights myself to champion what I know as truth: We learn to read by reading. In this simple truth, I have supported and watched hundreds of children (thousands, in truth) bud and blossom as readers. The exact journey and timeline of reading learning wasn’t and isn’t the same for all children. But, from my observations and interactions, a few common factors have become vital patterns in successfully nurturing growing readers.

In the last year or so, the ugly reading wars have once again become fonder for argument and division. Worst of all, these fights are political, commercial, and drive learning and teaching into the desert of odd programs which provide children with little or no actual reading. I try not to let this crush my heart but I must admit that I am flabbergasted that we continue to fight with one another over methodology when common sense so clearly and vividly illuminates the truth – To grow readers, children need to read. Period.

Independent reading leads to an increased volume of reading. The more one reads, the better one reads. The more one reads, the more knowledge of words and language one acquires. The more one reads, the more fluent one becomes as a reader. The more one reads, the easier it becomes to sustain the mental effort necessary to comprehend complex texts. The more one reads, the more one learns about the people and happenings of our world. This increased volume of reading is essential

Contact Us

ISS provides innovative professional development, school audits, and candidate recruiting for international schools around the world. Interested in learning more about how ISS can help with your needs? Drop us a line below and we’ll happily get back to you!

Because of our own book clubs and with the insights about how reading has often been a form of therapy for us, my sister-in-law Shelly and I started a book club for our sons when the boys were in first grade. Beginning with Lily’s Purple Plastic Purse by Kevin Henkes, these every four-to-six week gatherings throughout the boys’ lives continued until they were in early high school (when everyone’s schedules made meeting impossible). Our child-parent book club gave us a continuous vehicle to talk to the kids through the characters and problems of the books which would often have been too uncomfortable or hard for the children – or us more frankly – to deal with directly. The main ingredient of our child-parent book club was joy, an essential emotion all children need to tie with reading. As an empty nest Mama bear now, I treasure these book club memories and I think my son and nephew do, too.

To grow readers, children need to be trusted and respected to select their own reading texts. To grow readers, thinking and understanding must be paramount in our instruction while also giving each child responsive doses of phonics and conventions. We withhold nothing, we model the problem solving of reading new words, we trigger thinking skills and strategies by revealing our own openly and compassionately.

Because best practice literacy instruction is not highly commercial, because we cannot monetize the workshop model – apprentice style teaching, we are vulnerable. But please hear this – Good teaching and meaningful learning do not come from a worksheet or drill exercise. In From Striving to Thriving, Stephanie Harvey and Annie Ward (2017) emphasize this fact on the very first page. They note that “four decades of research have established that voluminous, pleasurable reading is key to literacy development” (p. 9). Intentional, protected time for independent reading within the school day or class period allows students opportunities to practice reading skills in a high-engagement, low-stakes environment. Students have a choice over the medium through which they develop reading skills, fostering true engagement in the act of reading (NCTE, 2019).

Let children see you read.

Children imitate what they see us giving time to in our own lives. By reading in front of growing readers, our actions really will speak louder than our admonishments. Seeing the adults they love to engage in reading acts as an invitation to children. Invite your children or students into living a literate life by sharing your reading habits openly.

When I began teaching, parent education workshops were part of each year’s teaching work. Not yet a parent myself, I turned to the parents of my students to craft some of their authentic needs and questions so that my efforts for parents were relevant and meaningful. One of the insights we all gained from these collaborations was the fact that the kids were not seeing us read because we engaged in our own reading after the children went to bed (or, in my case, outside of our class). We began to realize that this was a mistake and left children out of what was vital to so many of us. So, now I always read alongside students in classrooms and share my own reading time with my son, daughter-in-law, nieces and nephews. It’s an integral part of our relationships with one another.

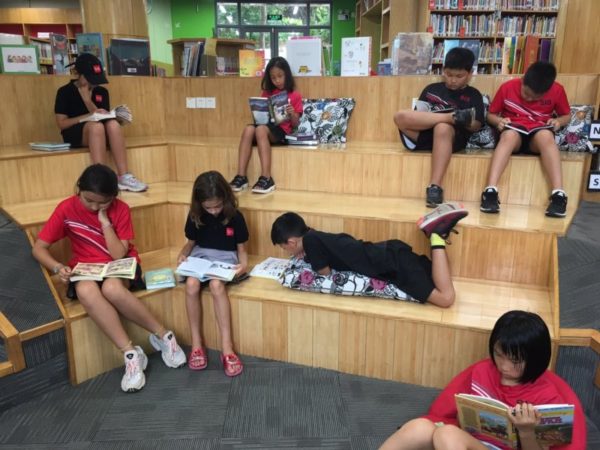

Weave reading into your classroom life and family life.

As an educator first and then as a mom and aunt, I have witnessed something lovely and remarkable: All children who grow up in families where reading is practiced and modeled become readers themselves. Yes, the transformation sometimes takes some time and the wait can cause us to become quite worried. But, if we do as Robert Frost advises – Surround youngsters with so many books that they stumble over them – we are marinating them in living a reading life. In the end, our invitations into the world of books and texts are seized, especially when choice and providing lingering time are honored.

By reading to and with children, you are giving them a quiet place and you are giving them a part of yourself no other activity can replicate or match. The intimacy, the shared thinking, the laughter, the awe, the bewilderment, and the sorrow, too – You now have common experiences which deepen your relationship and connection to one another. It’s one of the very best things we can do to nurture children’s hearts and it absolutely widens the mind.

I have been a member of two book clubs for over twenty-five years. One I enjoy with my husband Dave and three other couples. My other book club is a group of six fellow teachers and completely champions of my heart, especially because they stuck with me even when I lived overseas for several years. Not many friends hang with you like that. But book mates do. Just as books help me to dwell in the soul of another, talking with fellow readers increases my compassion by layering my knowledge of the world with theirs (Benson, 1996).

Reading should not be presented to children as a chore or duty. It should be offered to them as a precious gift.

Share how you read.

As you nurture growing readers – your own children or your students – reveal your how’s. How do you work to understand what you read? Share your internal dialogue by thinking aloud. Tell your growing reader/s about when rereading and how you ask questions as you read. Demonstrate your ways of knowing what is important as you read. In my case, I share reading sentence stems such as “I learned…” to determine importance as I read nonfiction and “I am feeling…” or “I am sensing…” to share how I identify importance when I read poetry.

Children of all ages mistakenly think that adults read perfectly and without effort. Sharing the hard work of your reading and your own problem solving skills as a reader are some of the best and most “Ah, ha!” provoking moments you will share together. Listen to how you talk to yourself before, during, and after reading. These words are your authentic reading scripts you can share with your children or students to nudge their own understanding work as a reader.

Reveal why you read.

Share why you turn to texts. This reading ritual is vital. It can take many a budding reader a few years to find her or his identity as a reader. Because reading is hard work and because some children do take and need some time to identify themselves as readers, reading will not always be your child’s or students’ first draft pick for their free time activities. This is a chief reason to openly and passionately share why you read to the growing readers of your life.

Years ago, I heard fellow Scotsman turned Coloradan Thomas Sutherland share the refuge he found in books as he was held captive for over six and a half years in Beirut. This has been true for me all my life, too. And, over the last four decades, I have interviewed hundreds of people about their reading lives and a clear “why I read” pattern has emerged denoting our intentions for reading as the golden compass. Show and tell the children in your life why you read. They need to hear these motivations.

From these few do’s, here are a few cautions for nurturing the literacy of growing readers:

Don’t ask your student or child to do anything as a reader that you don’t do yourself as a reader.

After reading a great book, I often tell a friend about the book and encourage others to read it. I don’t write a book report. I do read and enjoy book reviews. So, with my students and my own son, I encouraged book recommendations and sharing which occasionally turned into book reviews. But I never asked my kids to write a book report, create a diorama of their reading, or write about everything they read. These clerical tasks quickly turn children off to reading. Let them read as you and I do – read for pleasure, read for information, read to edify.

Don’t police your students’ or children’s choices in reading.

Rather, encourage and respect each child’s choices in reading. Choice is the greater energizer of literacy. Think about your nightstand table reading and those texts you choose to read on an airplane. We often read texts which, in fact, is at our easy, comfortable level. Reading demanding texts 100% of the time isn’t what we do as readers. We love a good piece in The New York Times, yummy recipes, or riveting sports articles, right? Pouring over the rich photography essays and design portraits in decorating magazines is a huge passion of mine. Are these cognitively rigorous or demanding for me? Probably not but they fuel my creativity and sense of possibilities in creating my own home and office environments. In other words, they are pure fun and joy for me. Why not encourage all children to bring this kind of joy reading into their own lives? Whether they choose to read graphic novels, unknown author science fiction, fifteen books about horses, action-packed comics, or art books full of rich photography, honor children’s choices as readers.

Many years ago, I heard Frank Smith say that a truly literate person is a person who not only can read but chooses to read, too. To help our children choose to bring reading into their lives, honor their voices and choices as readers. Model authentically your ways, joys, and struggles as a reader. Surround the children you love with so many books that they stumble over them. For my family, this means we have books in every room of our home and in our cars, too. Trust that by living literate lives as a family or in your classroom, your growing readers will turn to reading and embrace it as essential oxygen in their lives. Happy reading, happy connections, and happy sharing your reading with all the children in your world!

Read more about the importance of reading:

Allington, R. (2017). How reading volume affects both reading fluency and reading achievement. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 7(1), 13–26. Retrieved from https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/61https://www.iejee.com/index.php/IEJEE/article/view/61

Atwell, N. and Merkel, A. A. (2016). The Reading Zone: How to Help Kids Become Skilled, Passionate, Habitual, Critical Readers, 2nd ed. New York, NY: Scholastic Professional.

Barnhouse, D. and Vinton, V. (2012). What Readers Really Do: Teaching the Process of Meaning Making. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Beers, K. and Probst, R. (2017). Disrupting Thinking: What How We Read Matters. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Benson, L. (1996). Intellectual Invitations. International Reading Association.

Benson, L. (2001). Living a Literate Life. The Colorado Communicator. (25), 1 and 39 – 51.

Benson, L. (2002). Our Work: Developing Independent Reading. The Colorado Communicator. (26), 15-24 and 47.

Benson, L. (2011) in Almeida, L., et. al. Standards and Assessment: The Core of Quality Instruction. Englewood, CO: Lead and Learn Press.

Brooks, M. D., & Frankel, K. K. (2019). Authentic choice: A plan for independent reading in a restrictive instructional setting. Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy, 62(5), 574–577. doi:10.1002/JAAL.936

Fisher, Douglas and Frey, Nancy (2019). Show & Tell: A Video Column/Don’t Just Think Aloud, Think Along. Educational Leadership Vol. 77, No. 3.

Gallagher, K. (2009). Readicide: How Schools Are Killing Reading and What You Can Do About It. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

Gallagher, K. and Kittle, P. (2018). 180 Days: Two Teachers and the Quest to Engage and Empower Adolescents. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Harvey, S., & Ward, A. (2017). From striving to thriving: How to grow confident, capable readers. New York, NY: Scholastic.

Kittle, P. (2012). Book Love: Developing Depth, Stamina, and Passion in Adolescent Readers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Krashen, S. D. (2004). The power of reading: Insights from the research. Westport, CT: Libraries Unlimited.

Miller, D. and Moss, B. (2013). No More Independent Reading Without Support. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Miller, D. and Sharp, Colby. (2018). Game Changer! Book Access for All Kids. New York, NY: Scholastic.

National Council of Teachers of English/NCTE (2019). Statement on Independent Reading.

http://www2.ncte.org/statement/independent-reading/

Pressley, M. and Allington, R. (2014). Reading Instruction That Works: The Case for Balanced Teaching, 4th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Ripp, P. (2017). Passionate Readers: The Art of Reading and Engaging Every Child. London: Routledge.

Seravallo, J. (2015). The Reading Strategies Book: Your Everything Guide to Developing Skilled Readers. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

Short, K. G. (2011). Children taking action within global inquires. The Dragon Lode, 29(2), 50–59.

Sztabnik, B. (1/5/2017). Igniting a Passion for Reading: A veteran English teacher on the importance of choice, plus three tactics to keep high school readers engaged. Edutopia.

Tovani, C. (2000). I Read It But I Don’t Get It. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers.

10 Reasons Why Reading Is Important

11 Benefits of Books: Why Reading is Important

Jacobs, T. (June, 14, 2017). Lifetime of Reading Slows Cognitive Decline. Pacific Standard.

https://psmag.com/economics/lifetime-of-reading-slows-cognitive-decline-61800

Stories and Pictures

*Documentary film. Please note Director/Producer Joanna Rudnick is seeking Kickstarter funds to complete the film.